Our daily lives remind us of the importance of knowing history. This is not only true for those of us with contemporary regional experiences, but is also applicable more broadly, especially when looking at global currents. We are repeatedly confronted with political practices that have been proven to be unproductive and socially harmful. History may not repeat itself, but mistakes do, and this is reminiscent of a circular return to where we started. With the constant question, for how long?

It is no coincidence that experiences do not teach us enough useful and purposeful solutions. Although there are many causes, part of the explanation also lies in the way history is taught. And it seems that the problem will become more complex as learning (as part of self-education) is transferred to the digital world, in which there are still not enough authorities in the field of historical science, and prejudice is reproduced even faster and easier.

We historians have been working for a long time to improve methodological approaches to the modern study of history, but this remains separate from the modern digital needs of young generations. The situation is additionally complicated by the fact that history is one of the most abused sciences – and is in a constant struggle with dominant nationalist policies. And now the struggle needs to be expanded to the digital space – this is both a new difficulty, but also an opportunity to enable modern approaches to historical topics in democratized spaces (as democratic as an algorithm can be!) and, most importantly, to provide relevant answers to new-old questions in the world of digital interaction. If we don’t do it, AI will. And we shouldn’t forget that artificial intelligence learns only from digital content. The conclusion is self-evident.

In addition to all this, another component complicates our work. The way history in the region is still written and read is influenced by nationalist policies, and thus (over)burdened with national narratives, it is a shell, emptied of meaning. Full of national topos – designed to be reproduced, without asking questions. And it is no coincidence – a student who understands processes, and who is able to connect similar patterns in different countries and eras – is also able to ask questions about the society in which they live. The shortened attention span of young people does not have to be an obstacle to quality learning, although teachers often complain about it – it just requires us to take different approaches in teaching and presenting historical narratives and episodes. The digital world gives us countless opportunities here, and that is why we boldly step into a terrain that is equally ours – the modern era calls on us all to adapt to new needs.

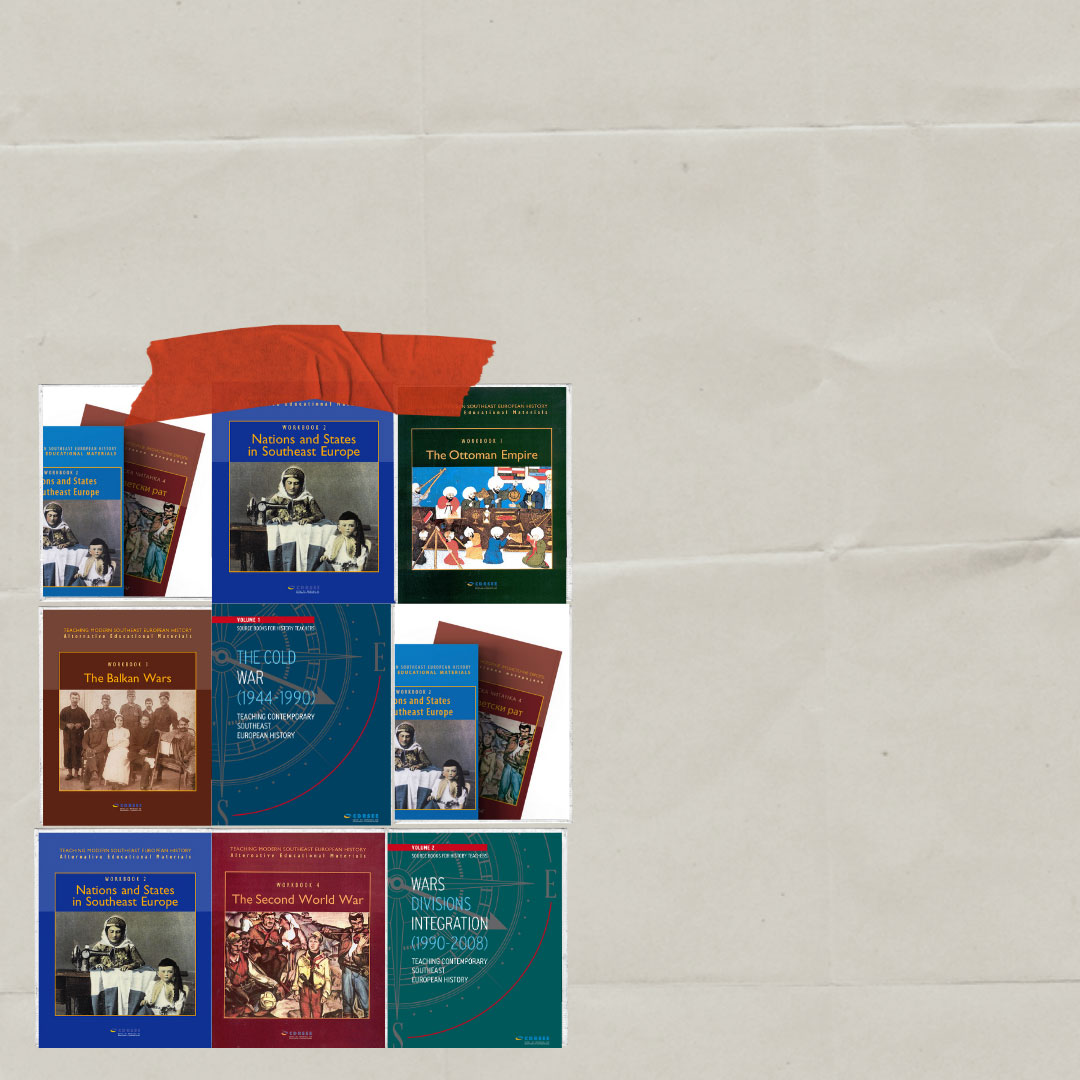

Recognizing contemporary social shortcomings, new approaches (are they even new!) become not only a need, but also an imperative. The Joint History Books project (jointhistory.net) is one of the most important steps in the process of unifying the understanding of the history of common spaces. Because space and historical processes connect us all into a single whole, and national agendas divide us into separate, unrelated, conflicting camps.

Six books compiled so that an experienced history teacher can use them in class as a significant improvement in the quality of teaching, they are also there for independent use by students – each historical unit can be better understood if they are also familiarized with the historical sources of the peoples left out from the national perspective. Another advantage is that all the textbooks are available in local languages, which makes reading and understanding easier.

How does it work in practice? An example from the textbook dedicated to the emergence of nation-states in the Balkans. In national curricula, we have a constant glorification of national liberation. The birth of a new nation-state is placed in sharp contrast to the difficult past, which makes the liberation more magnificent, and the methods of struggle in that process perfectly legitimate, and admirable. In such a refined narrative, there is no room for the aspirations of other peoples who experience their destiny as equally magnificent and chosen. In such an environment, other peoples and their aspirations become not self-evident as part of the same process – but a hindrance. In this way, national prejudices are created, which are then justified for generations, and become part of a whole that is not subject to questioning.

There are many examples, and Joint History Books come from a starting position of breaking entrenched narratives and opening up space for understanding them from different perspectives. By expanding the mold for understanding historical reality, we actually understand the world around us better. In a world of understanding, there is less room for prejudice, manipulation and abuse. From now on, the books are also available in the digital world, and interaction with historians has been established through various channels on social networks. In this way, we contribute to bringing quality historical content closer to young generations through an interactive approach and direct contact – where they spend most of their time. Thus, the circle of democratization of knowledge closes (or opens!), simultaneously while leaving offline spaces and nationalist curricula. The 21st century will be a century of challenges. But we are ready.

Sanja Radović

The author is a historian and a collaborator on the Joint History Books project